By: Michelle Francis, LCSW-QS, DBH Candidate at Cummings Graduate Institute for Behavioral Heath Studies, written for the course DBH: 9012: Population Health

PHM: Chronic Kidney Disease and Depression

Introduction

Imagine the mental agony of having to wait on edge for months or more commonly, years, on the kidney transplant list for a match to receive a new kidney. This is the reality for more than 100,000 Americans. According to the National Kidney Foundation (2023), the average wait time to receive a new kidney is about 3-5 years, and the wait may be longer based on one’s location in the country. Given these statistics, it is evident as to why an individual with Chronic kidney disease (CKD) may also suffer from depression. This literature review will explore the relationship between CKD, depression, and treatment modalities that serve as the best outcomes.

Section I: Literature Review

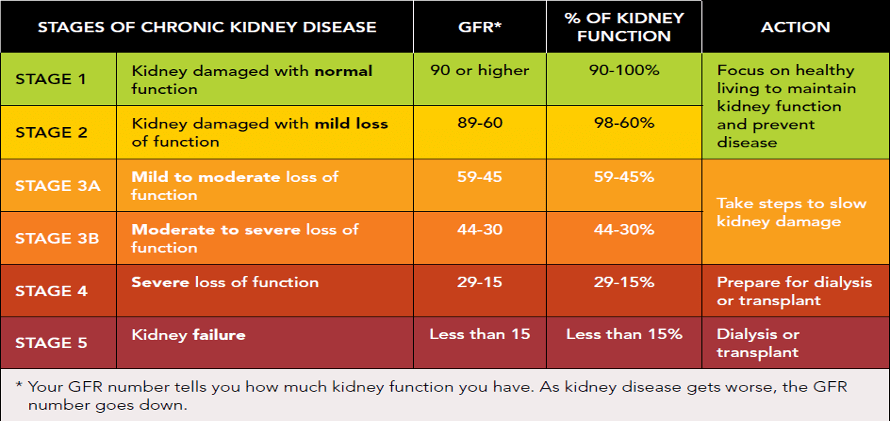

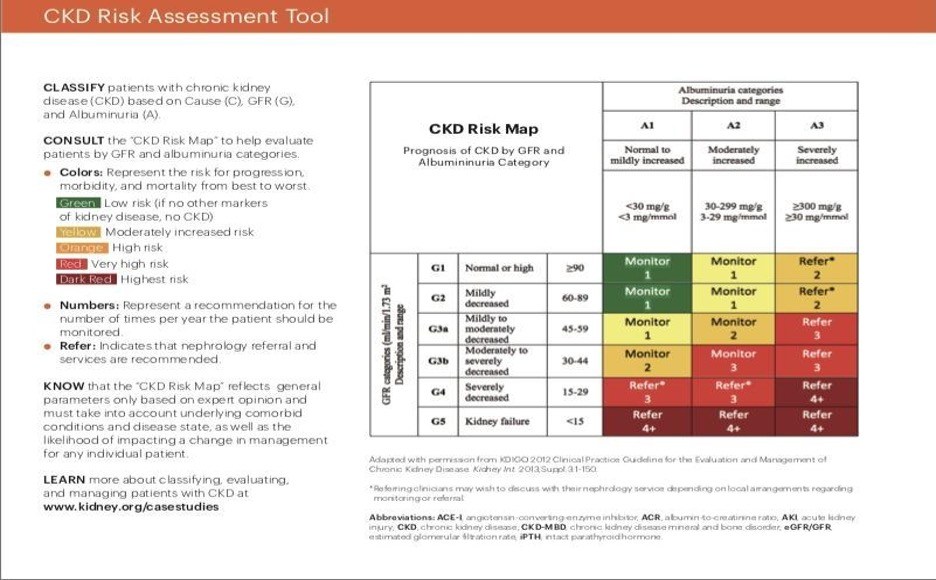

Chronic kidney disease is the 16th leading cause of lives lost worldwide. In the United States, an estimated 37 million people, or about 15% of the population are diagnosed with CKD, which equates to 1 in 7 individuals (Chen, 2019). Ammirati (2020) explains that a CKD diagnosis is determined in adults when “An adult patient present, for a period equal to or greater than three months, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) lower than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, or GFR greater than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, but with evidence of injury of the renal structure” (Ammirati, 2020). In the article “Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis and Management”, Chen (2019), emphasized that CKD is commonly caused by diabetes or hypertension, which accounts for 3 out of 4 new cases. CKD is often underdiagnosed or underrecognized by healthcare professionals.

Risk Factors

CKD is more prevalent in low- and middle-income communities than those who are within a higher socioeconomic status. In both depression and CKD, genetic risk factors are common indicators. Oftentimes, if a family member has/had either condition, the likelihood of another relative being diagnosed with CKD and/or depression increases. Additionally, environmental conditions such as air pollution and pesticides are risk factors that also need to be taken into account with folks who are diagnosed with CKD (Chen, 2019).

Unfavorable Outcomes

In the article, “Association between sedentary behavior and depression in US adults with chronic kidney disease: NHANES 2007-2018”, Lui et al. (2023) completed a cross-sectional study to learn more. Their research had a total of 5,205 adult participants who were diagnosed with CKD. The study took place between 2007-2018. Participants completed the PHQ-9 at intervals, which found that depression increases the risk of adverse clinical outcomes in patients with CKD. Furthermore, Chun-Yi et al., (2022), had 151 subjects in their research, “Frailty as an Independent Risk Factor for Depression in Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study.” The participants were all diagnosed with end stage renal disease and were screened using the geriatric depression scale. The research concluded that “patients with CKD, frailty independently correlated with a higher probability of having depression” (Chen, 2022). Essentially, though patients received medical care to treat CKD, their depressive symptoms consequently impact their overall wellbeing.

Prevalence and Occurrence

CKD is slightly more common in women than men. Of those who are diagnosed with CKD, Black Americans are impacted the most, followed by non-white Hispanics (CDC, 2022). As mentioned, depression impacts the quality of life negatively for individuals who are diagnosed with CKD. In the article, “Chronic kidney disease: quality of life, anxiety and depression in a group of pre-dialysis patients”, 155 participants who had CKD completed a survey. The purpose of the study was to determine the prevalence of mental health disorders and the impact of quality of life for folks who are diagnosed with renal failure. The patients completed two questionnaires, which were namely the SF-12 which is also known as the “general state of health” as well as the HADS, which screens for anxiety and depression, (CKD, 2022). The results showed that 65% of patients had a low quality of life, which was associated with health, and difficulties in wanting to participate in daily activities. The study also revealed that all mental health disturbances “were higher in females and in patients with more comorbidities”(CKD, 20222). Furthermore, depression was also more frequent in elderly folks.

Mortality

Muscat et al. (2020) wrote the article “Illness perceptions predict mortality in patients with predialysis chronic kidney disease: a prospective observational study.” The researchers evaluated whether illness perceptions impact mortality in incident predialysis CKD patients. 200 CKD participants were followed for nearly 4 years between 2015-2019 and 43 participants died during the study. The researchers believe that illness perception impacted mortality rate in these patients as their mental health may have also been affected as well, which also led to death. Furthermore, Wang et al. (2021) completed the study “Effect of Marital Status on Depression and Mortality among Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2014.” They found that unmarried CKD patients had worse outcomes than those who were married and were at a greater risk of experiencing depressive symptoms. All in all, the researchers concluded that mortality rate and depression are heavily influenced by one’s marital status for patients who are diagnosed with CKD.

Cost

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) notes that about 360 people begin dialysis everyday due to kidney disease. Treating CKD is extremely expensive. “Medicare beneficiaries with CKD cost $87.2 billion and treating people with end stage renal failure cost an additional $37.3 billion” (CDC, 2022). CKD is an incurable illness, therefore, while there are ways to slow down the progression of CKD, the condition will continue to be a major cost for the healthcare system, especially since it is one of the leading causes of deaths. League et al. (2022) took a closer look at cost concerns and disparities in their study “Assessment of Spending for Patients Initiating Dialysis Care”. A cohort study was conducted between 2012-2019 to assess “the amount and types of increases in health care spending for privately insured patients associated with initiating dialysis care” (League et al., 2022). The researchers found that private insurance cost the system nearly 3 times as much compared to Medicare users per person. It is important to note that most individuals who are receiving dialysis are covered under Medicare, therefore, Medicare numbers will be higher systematically as noted above. However, despite which insurance one has, the healthcare system pays the price in the end.

Costly medical bills due to CKD lead to depression. The average American is struggling daily to make ends meet. On top of that, folks have to worry about keeping their insurance active, making co-payment at the start of most provider visits to ensure that they are able undergo dialysis as a way to improve their chances of surviving.

The Need

The research shows that there is a strong link between chronic kidney disease and depression. The mental distress is evident at the initial diagnosis and lasts through the course of treatment and may even lead to mortality. Several researchers completed surveys using the PHQ-9, the geriatric depression scale, and other assessments which determined that many patients are depressed while receiving dialysis. However, the studies lacked significant follow-up on the need for co-cormid treatment for CKD and depression. There is little to no suggestions regarding how to improve one’s mental health while getting their basic medical needs met, which is receiving dialysis. In their article, “Effectiveness of Wellbeing Intervention for Chronic Kidney Disease (WICKD): results of a randomized controlled trial”, Dingwall et al., stated “Few studies have investigated the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for people with end stage kidney disease”, (Dingwall et al., 2021). These researchers found that patients who are on dialysis that talk to people about their wellbeing and their kidney health showed signs of increased mental well-being.

An integrated setting is needed where both conditions can be treated simultaneously. It would be beneficial for dialysis centers to have several mental health professionals on site to aid patients with all of the feelings that come with being diagnosed with a chronic condition. Furthermore, talk therapy is a great intervention to start with because patients can say as as little or as much as they want as they navigate through their stages of change regarding renal failure. Another provider that would be beneficial in this integrated setting is a wellness coach. Due to personal or cultural reasons, some people do not feel comfortable opening up about their mental health concerns. Therefore, a wellness coach could focus on other aspects of the client’s life such as nutrition, physical health, amongst other things that will also boost the patient’s mental health and reduce the depressive symptoms. Moreover, a psych provider should also be on site as well. Mental health cannot be categorized as one-size fits-all. It is a reality that some patients may need psychopharmacological therapy to aid with their well-being. Hence, antidepressants are another intervention that may aid folks with CKD and depression as they navigate through their reality.

Section II: Intervention Proposal

As noted in section 1, an estimated 15% of the United States population are diagnosed with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Studies indicate that it is common for folks who are diagnosed with CKD to also experience symptoms of depression. Depressive symptoms include a change in one’s sleep pattern, weight loss or weight gain, increased stress levels, and an overall decline in their quality of life. This PHM proposal will focus on the implementation of the Lifestyle Improvement Amenities (LIA) program for CKD and depression simultaneously as a way to improve the patients’ quality of life because our mental and medical well-being are equally important.

Patient Population

The proposed intervention will target adults who are diagnosed with chronic kidney disease and are also at risk for developing depressive symptoms. The intervention will be implemented in five PCP offices located in Orlando, Florida. On average, each office sees about 2,000, adult aged patients annually. The five offices combined see 10,000 adults per year. Chen et al. (2019) notes that about 1 in 7 Americans are diagnosed with CKD and about 23% of CKD patients also have depression. Based on the 10,000 adult patients at the five PCP offices, 1,400 patients will be diagnosed with chronic kidney disease and 322 will have combined depression (Mosleh, 2020).

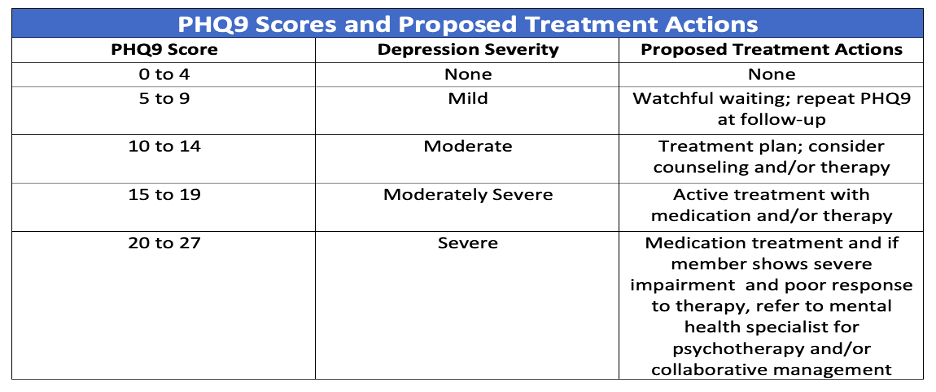

Population Identification

The electronic health record (EHR) along with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) will aid with patient identification. Patients who are eligible must have a CKD diagnosis. Once CKD patients are identified, medical staff at the PCP offices will assist by administering the (PHQ-9) either in office or via phone. Sun et al. (2020) notes that the PHQ-9 is a rapid and effective screening, diagnosing, monitoring and measuring the severity of depression and has been widely used in community-based settings, in the general population, and among people with physical diseases (Sun, 2020). A report will be run in the EHR to filter the PHQ-9 scores. Patients who score 0-4 indicate that there is none to minimal depression present. Scores 5-9 indicate that there is mild depression present. Those who score 10-14 show signs of moderate depression. Furthermore, if scores fall between 15-19, the patient may be exhibiting moderately to severe symptoms. Lastly, if scores are 20-27, it is an indication that the patient may be severely depressed.

Population Engagement

Upon narrowing the data, a team of behavioral health clinicians along with PCP office staff will contact patients who score a 5 and above on the PHQ-9 assessment to schedule a 15- minute consultation. During the actual consultation appointment, the clinician will introduce the program entitled, Lifestyle Improvement Amenities (LIA). The clinicians will assess the patients further via phone by asking questions about how they manage their CKD, lifestyle choices such as nutrition, fitness routine, stress levels, and additional questions about their depressive symptoms. The clinician will explain the benefits of the program which include development of coping skills, stress reduction, improvement of mental health symptoms, among other amazing health outcomes.

If the patient agrees to participate in the program, the clinician will send a follow-up email with a summary of their conversation. The email will contain a brochure about the program that includes dates, times, location, and all of the services that will be available to the patient. The email will also have the contact information of the clinician if the patient were to have any additional questions and need to reach out.

Setting

The setting for the LIA program will be at an integrated health care clinic that is central to the five PCP offices. It is important that patients who want to utilize this service are not disadvantaged due to location. The clinic will consist of a PCP, nephrologist, nurse practitioner, wellness coach, clinical therapists, and the DBH. The LIA program will take place over the course of 6 weeks. During the 6 weeks, all service providers will be onsite daily. The patient will have the ability to receive wraparound behavioral health services to improve their quality of life.

Enrollment, Participation, and Completion

As noted in section 1, the research around CDK and depression only discusses the prevalence of the combined conditions as opposed to how to treat them together. Researchers identify that treating both conditions together will yield better outcomes, but there is a lack of studies completed to conclude the suggested outcomes. Shirazian et al. (2016) expressed that “unfortunately few studies have examined the safety and efficacy of treating depression in patients with CKD, and these studies are limited by small sample sizes, lack of control groups, and selection and drop-out bias” (Shirazian, 2016). Due to the lack of research around program outcomes for patients with CKD and depression, the LIA program is extremely useful for this population.

The LIA program has a duration of 6 weeks, with patients expected to attend the clinic weekly to attain the best outcomes. Patients are allowed to miss one week, though risk disenrollment if they should miss 2 or more weeks. During each visit at the clinic, the patient is expected to see at least two service providers onsite. This way, the patient is receiving care in more than one aspect of their life weekly. If a patient only wants to see one provider during a visit, they will be allowed to return the following week, but they would need to see a different provider. For example, if they saw the PCP this week, and they are adamant that they only want to see one provider per week, they would need to have a session with either the clinician, wellness coach, or psych provider the following week. Additionally, their participation would be reduced from 100% to 50% each week if they do not follow the program requirements of seeing at least two providers.

Section III: Assessment, Risks, Interventions, and Outcomes

Assessments

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is commonly identified through routine screenings. Providers complete various variations of urine and blood tests to determine the diagnostic results of CKD. The screening tools may be able to determine which treatment option is best for the patient and which of the 5 stages of CKD a patient falls within. The patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) will be used as an assessment and diagnostic tool for depression.

Urine Test. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (2022), one of the most common early warning signs of CKD is when protein leaks into the urine. Protein levels in the urine can be determined by the dipstick urine test and the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio test (UACR) (CDC, 2022). Providers use the dipstick as a way to look for a protein produced by the liver called albumin, in the urine. This test is completed by placing a dipstick into the urine. The dipstick test does not provide an exact measurement of albumin, but it allows providers to know if the levels are abnormal. The dipstick changes colors if levels are above normal, in which providers may order additional tests.

The urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio test alerts providers to know how much albumin passes into the urine over a 24-hour period. If the results are 30 or above, it may mean that the patient has kidney disease. It is important for providers to repeat this test to confirm that the results are correct (CDC, 2022).

Blood Tests. Blood tests are used to determine how well the kidneys are functioning and along with how quickly the waste is being removed from the body (CDC, 2022). The most commonly used blood tests are the serum creatinine and glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Firstly, the serum creatinine blood test measures the amount of creatinine in the blood. If the kidneys are not functioning normally, the serum creatinine level goes up in the patient’s body. Results with creatinine levels more than 1.2 for women and more than 1.4 for men may be a sign of kidney abnormality. It is important to note that normal levels are determined by one’s demographics such as sex, age, and the amount of muscle mass your body has. Therefore, this test does not use a one-size-fits approach for determination as there are variables to consider.

The CDC notes that “the Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) blood test measures how well the kidneys remove waste, toxins, and extra fluid from the blood” (CDC, 2022). The serum creatinine level, and the patient’s demographics are used to calculate the GFR number. Similarly, to the serum creatinine test, the patient’s sex, and age, along with other identifiable factors determines what constitutes a normal GFR number. If the GFR is low, that means that the kidneys are not functioning as well as they should.

CKD Scoring. The CDC (2022) notes that for patients with a GFR score of 60 or above with a normal urine albumin test, the patient does not have kidney disease. However, the patient should schedule a follow-up test for monitoring and to ensure that the results remain the same. Furthermore, a GFR number less than 60 may be an indication of kidney disease and treatment options should be discussed with the provider. There is a valid indication that the kidneys are failing if 15 patients have a GFR score of 15 or less.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9. The PHQ-9 is a brief yet useful tool in clinical practice used for screening, diagnosing, monitoring, and measuring the severity of depression. The PHQ-9 incorporates the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) to determine the depression diagnostic criteria with other common major depressive symptoms into a brief self-report tool.

Risk Stratification

Risk Stratification

Adults diagnosed with stage 1, stage 2, stage 3a, stage 3b, stage 4, and stage 5 chronic kidney disease will be invited to participate in the study. Adults with stages 1 and 2 of kidney damage but mild depression cut off will be placed at the level one of intervention. Adults who are within stages 3a and 3b cut off but with to moderate to moderately severe depression cut off will be placed at the level two of intervention. Adults with stage 4 and stage 5 chronic kidney disease with severe depression cut off will be placed at the level three one of intervention. Adults within stages 4 and 5 of CKD but with mild to moderate depression will be placed at intervention level two. Adults within stages 1, 2, 3a, and 3b but with severe depression will be placed at the level three of intervention.

Intervention based on Levels of Care

Level One Intervention. Patients at this level exhibit minimal loss of their kidney function and mild depression. They will be provided with educational resources about the importance of lifestyle changes. These patients will be encouraged to incorporate physical activity into their daily routine. If the patient smokes, they will be encouraged to quit smoking. These patients will be educated on the importance of a balanced diet. They should stay within their targeted cholesterol range and reduce their salt intake. The patients will be instructed to eat more fruits and vegetables as well engage in activities that they enjoy. The purpose of this is to maintain healthy habits to maintain kidney function.

Level Two Intervention. The patients at this level are exhibiting moderate to moderately severe symptoms of depression. They will be provided with all of the resources given to level one patients. The patients at this level will be able to see two providers of their choice on site each week. The providers include a wellness coach, a psychiatric nurse practitioner, the behavioral health clinical (BHC)/therapist and a PCP. Level two patients have the ability to rotate between providers as a way to expand their knowledge about their physical and mental health concerns. It is important to note that level two patients who want to complete therapy sessions must sign up during week 1 and should see their therapist on a weekly basis as slots are limited. Furthermore, since the program is only for 6 weeks, it would not be in the best interest of the patient for them to skip therapy sessions given the limited timeframe. However, if a patient expresses that they do not want to return to therapy after one or a few sessions, they can return to seeing two other providers of their choice.

Level Three Intervention. Patients at this level are experiencing severe symptoms of depression. These patients will receive all of the resources provided to patients at level one. Similar to level two, they will be able to see two providers weekly. However, one of their providers will automatically be the BHC due to the severity of their depression. The BHC will see these patients weekly for six consecutive weeks for their mental health concerns. The sessions will be one hour in length. The first session will serve as a baseline. A treatment plan will be created by the BHC and the patient together to determine what the patient would like to work on and accomplish by the end of the six weeks. The final session will be considered the termination session. The treatment plan will be reviewed together, the patient will recap what they learned over the six weeks, express which coping skills they will continue to utilize upon termination, and the BHC will make referrals if deemed necessary. If it is determined that level three patients are in need of a continuation of care, the providers in the program will work together to formulate a plan that is unique to each patient for the best health outcomes.

Intervention Anticipated Clinical Outcomes

This section explains the anticipated patient outcomes of the LIA program.

- The PHQ-9 scores are expected to decrease at least one risk stratification level in 50% of the patients who participate in the program at all three levels of intervention three months from the initiation of the intervention. This is anticipated because the patients will learn new skills to aid with their mental health concerns throughout the treatment process and about half of them will continue to use said skills after the conclusion of the program.

- 50% of participants will increase their physical activity by incorporating 30-minutes of exercise into their routine 3 times per week 6 months from initiation of the intervention. This outcome is anticipated because exercising more is a common goal for these patients. Therefore, setting a goal to exercise three times per week for 30 minutes appears to be attainable.

- 25% of participants will reduce their salt intake by following the renal diet given to them by their provider during the 6-week program. This outcome is anticipated because the patients are very aware that their diet plays a huge role with the expected outcomes for kidney disease. However, it is very difficult to incorporate and maintain healthy eating habits if it is not something that is practiced daily. Therefore, it is expected that about 25% of the participants will try to follow their provider’s recommendations during the period of the intervention.

- 30 % of participants in level two and level three will replace harmful coping skills such as isolation and snacking with healthier options such as going for a walk or calling a friend three times per week during the 6 weeks of the program. This outcome is anticipated if participants actively try to replace non-conducive habits with healthier, morale boosting options.

- 30 % of participants will engage in a hobby at least once a week during the duration of the program as a way to decrease their mental health symptoms and boost their mood. This outcome is anticipated because when people are able to indulge in activities that they enjoy, it yields positive outcomes.

Section IV: Costs, Savings, ROI

Intervention program cost

The Table below shows the breakdown of the cost for the LIA project. Section II identified that about 322 patients would be diagnosed with CKD and depression. Of that total number, 40% (128) are participants in this study. It is important to note that listed contracted providers are only on-site for 30 hours per week except for the DBH and the receptionist. The contracted providers are able to coordinate their hours with their scheduled appointments. Therefore, they are not needed for a 40-hour work week. On the contrary, the DBH and the receptionist are on-site for 40 hours weekly. The receptionist is expected to always be present at the front desk at all times given that appointments are scheduled for mornings and afternoons. The DBH is the head of this project, therefore, being on-site throughout the day is essential to answer questions, gather data, and oversee all aspects of the LIA project. Additionally, all providers, the DBH, and receptionist are employed as contractors, therefore, benefits will not be provided. The total cost of this 6-week proposal is $149,742.82.

Table 2: Supplies

| Component | Quantity | Cost Per Unit | Total Cost |

| Copy Paper | 1 | $5.32 | $5.32 |

| Ink | 2 (color cartridges kit) | $45 | $90 |

| Total | $95.32 | ||

Table 3: Space Rental & Utilities

| Component | Quantity | Cost Per Unit | Total Cost |

| Space Rental | 6 weeks | $625/ week | $3,750 |

| Electricity | 6 weeks | $300/ month | $450 |

| Water | 6 weeks | $125/ month | $ 187.50 |

| Total | $4,387.50 | ||

Table 4: Salaries

| Component | Quantity | Cost Per Unit | Total Cost |

| PCP Salary | 180 hours | $125/ hour | $22, 500 |

| Nephrologist Salary | 180 hours | $140/ hour | $25,200 |

| APRN Salary | 180 hours | $50/ hour | $9,000 |

| Mental Health Therapist Salary (X3) | 180 hours (x3) | $100/ hour | $54,000 |

| Wellness Coach | 180 hours | $32/hour | $5,760 |

| DBH Salary | 240 hours | $100/hour | $24,000 |

| Receptionist Salary | 240 hours | 20/hour | $4,800 |

| Total | $145,260 | ||

Medical service utilization (pre- and post-intervention), cost and cost savings

Pre-Intervention Cost. The CDC (2022) notes the United States spends an average of $120 billion annually on patients who are diagnosed with chronic kidney disease, including end stage renal. Given that about 37 million Americans are diagnosed with CKD, with all things considered, including hospital visits, medical appointments, and other medical related expenses, this equates to about $3,243 in annual healthcare spending per person. This number is just an average because the cost for folks who are in stages 4 and 5 is higher compared to those in the earlier stages of CKD.

Post -Intervention Cost. As previously mentioned, there is limited data available regarding quality of life outcomes when CKD and depression are treated together. Please note that this intervention will not and does not intend to replace all medical costs and visits associated with CKD as well as the therapeutic interventions. However, the goal of this proposal is to reduce annual healthcare costs for CKD patients in the United States.

The average nephrologist visit in Florida is between $119 (Sidecar Health, n.d.) The average PCP visit is between $171 (Brooks, 2023.). Additionally, the average cost of mental health therapy in Florida is between $100-$200 per hour (Brafman, 2023). The average cost of a wellness coach in Florida is about $32 per hour (Salary, 2023). Lastly, the average APRN hourly wage is about $48 (Zip, 2023).

On average most CKD patients see their nephrologist about 4 times per year. Therefore, the cost to see this provider for the year would be about $476 CKD patients who see their PCP about two times annually; the yearly spending to visit this provider is estimated at $342. There is little to no data regarding how much a CKD patient spends to see a life coach, mental health therapist, and APRN. Therefore, the estimated cost for each of these would vary. For the purpose of this proposal, the CKD patients would see the life coach once monthly, which would result in an annual cost of $384. The APRN would like to be seen during the PCP visit, if at all. Therefore, the cost of that provider would be at most $100 for the year. Mental health therapy is vital given that the CKD patients are struggling with depression. On average, the mental health provider would be seen at least once per month with an average cost of $100 or an annual cost of $1,200. If the CKD patient were to see all providers listed, at the suggested intervals, it would cost them about $2,502 yearly.

Cost Savings. The average CKD patient costs the healthcare system $3,243 per year (CDC, 2022). If the patients were to see all providers listed and only seek mental health services once per month, that would result in an annual saving of $741 per person or nearly $27.5 billion. It is important to note that not every CKD patient has mental health concerns. As mentioned previously, 23% of CKD patients struggle with depression. Therefore, CKD patients who struggle with depression would save the healthcare system $6.325 billion annually.

ROI. The suggested intervention proposal costs a total of 149,742.82 over a 6-week period. However, if this proposal was to be implemented for one year it would cost $1,297,771.11. It is important to note that providers would be seen on a weekly basis during the intervention period. However, long-term, it is not cost effective. Therefore, if the 128 participants were to see the neurologist four times per year, the PCP and APRN, twice per year, and the life coach and mental health therapist once per month, it would cost them $320,256 for the entire year or $36,952 for six weeks. This results in a yearly return on investment of $977,515.11 or a six week return of $112,790.82.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Chronic kidney disease impacts millions of Americans. CKD patients take the necessary steps to care for their medical needs, but about 23% of those who are diagnosed with CKD experience depression-like symptoms. The LIA project should be an indication to dialysis centers, PCPs, and nephrologists that they should seek partnership and collaboration with mental health providers. The LIA project shows that even though chronic kidney disease is a terminal illness, treatment yields favorable outcomes when all aspects of their well-being are addressed. This PHM proposal indicates that when providers work together in an integrated care setting, patients receive positive results. Overall, this proposal would save the healthcare system millions of dollars and improve both the mental and physical health of CKD patients.

References

Agrawaal, K. K., Chhetri, P. K., Singh, P. M., Manandhar, D. N., Poudel, P., & Chhetri, A. (2019). Prevalence of Depression in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease Stage 5 on Hemodialysis at a Tertiary Care Center. JNMA; Journal of the Nepal Medical Association, 57(217), 172–175.

Ammirati, A. L.. (2020). Chronic Kidney Disease. Revista Da Associação Médica Brasileira, 66, s03–s09.

Brooks, A. (2023, August 30). Primary Care Doctor Visit Cost Without Insurance In 2023?Mira. https://www.talktomira.com/post/how-much-does-primary-care-cost-without-insurance

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, February 28). Chronic Kidney Disease Basics. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/basics.html#:~:text=In%20the%20United%20States%2C%20diabetes,cost%20an%20additional%20%2437.3%20billion

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, March 24). Kidney Testing: Everything You Need to Know. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/publications-resources/kidney-tests.html#:~:text=A%20UACR%20test%20lets%20the,twice%20to%20confirm%20the%20results.

Chen, T. K., Knicely, D. H., & Grams, M. E. (2019). Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis and Management: A Review. JAMA, 322(13), 1294–1304.

Chronic kidney disease. (2022, November 25). Chronic kidney disease. BMJ Best Practice. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/84

Chronic Kidney Disease: Living With Kidney Disease. (2021, May). Stages of Kidney Disease. Figure 2. https://cl.kp.org/mas/operations/PatientCareResources/CKD-Microsite.nohf.public.html?accessvia=copyurl

Chronic Kidney Disease: Quality of life, anxiety and depression in a group of pre-dialysis patients. (2022). Giornale Di Clinica Nefrologica e Dialisi; Vol. 34 No. 1 (2022): January-December 2022; 44-50.

Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States. (2021). CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/pdf/Chronic-Kidney-Disease-in-the-US-2021-h.pdf

Chun-Yi Chi, Szu-Ying Lee, Chia-Ter Chao, & Jenq-Wen Huang. (2022). Frailty as an Independent Risk Factor for Depression in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study. Frontiers in Medicine, 9.

CKD Risk Assessment Tool. (N.D.) Figure 1. https://www.kidney.org/sites/default/files/01-10-7027_ABG_HeatMap_Card_3_0.pdf

Dingwall, K. M., Sweet, M., Cass, A., Hughes, J. T., Kavanagh, D., Howard, K., Barzi, F., Brown, S., Sajiv, C., Majoni, S. W., & Nagel, T. (2021). Effectiveness of Wellbeing Intervention for Chronic Kidney Disease (WICKD): results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Nephrology, 22(1)

League R.J., Eliason, P. McDevitt, R.C., Roberts, J.W., Wong, H. (2022, October 28). Assessment of Spending for Patients Initiating Dialysis Care. JAMA Netw Open.,5(10)

Liu, L., Yan, Y., Qiu, J., Chen, Q., Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., Zhong, X., Liu, Y., & Tan, R. (2023). Association between sedentary behavior and depression in US adults with chronic kidney disease: NHANES 2007-2018. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1)

Mosleh, H., Alenezi, M., Al Johani, S., Alsani, A., Fairaq, G., & Bedaiwi, R. (2020). Prevalence and Factors of Anxiety and Depression in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis: A Cross-sectional Single-Center Study in Saudi Arabia. Cureus, 12(1)

Muscat, P., Weinman, J., Farrugia, E., Camilleri, L., & Chilcot, J. (2020). Illness perceptions predict mortality in patients with predialysis chronic kidney disease: a prospective observational study. BMC Nephrology, 21(1), 537.

Shirazian, S., Grant, C. D., Aina, O., Mattana, J., Khorassani, F., & Ricardo, A. C. (2016). Depression in Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease: Similarities and Differences in Diagnosis, Epidemiology, and Management. Kidney international reports, 2(1), 94–107.

SideCar Health. (N.D.) Cost of nephrologist visit by state. https://cost.sidecarhealth.com/c/nephrologist-visit-cost

Stemmle, C. (2022). 13 SMART Goals Examples for Depression and Anxiety. Develop Good Habits. https://www.developgoodhabits.com/smart-goals-depression/

Sun, Y., Fu, Z., Bo, Q., Mao, Z., Ma, X., & Wang, C. (2020). The reliability and validity of PHQ-9 in patients with major depressive disorder in psychiatric hospitals. BMC psychiatry, 20(1), 474.

Wang, Z., Cheng, Y., Zhang, N.-H., Luo, R., Guo, K., Ge, S.-W., & Xu, G. (2021). Effect of Marital Status on Depression and Mortality among Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2014. Kidney Diseases, 7(5), 391–400.

WU, S. (N.D). Comparing PHQ9 Scores. RPubs. Figure 3. https://rpubs.com/suwu1219/634469

ZipRecruiter. (2023). Nurse Practitioner Salary in Florida. https://www.ziprecruiter.com/Salaries/Nurse-Practitioner-Salary–in-Florida